Domenico Gnoli, everyday metaphysics

Waist line, Domenico Gnoli, 1969

This Italian artist Domenico Gnoli (1933-1970), residing in New York, has a pictorial practice that is close to Pop art. He owes his style to his frequentation of the masters of Italian painting in his hometown, Rome, where he grew up under the influence of his father, an art historian. After having done illustration and scenography, he devoted himself to painting souvenirs of the details of his Roman daily life in gigantic formats. He focuses on patterns when they are a priori the most insignificant, but they are in reality extracts of the essence of Rome; he thus gives a magical value to everyday attributes. And this very peculiar view creates a mystery about the hidden part of the scene. The care of his pictorial treatment is in the image of the situations depicted. Not a hair protrudes from the combed heads, not an armchair reveals a disordered interior. Everything is in its place, each person is chosified, each painting is metaphysical in the sense that other artists have experienced before him and one inevitably thinks of Giorgio de Chirico or Magritte. Domenico Gnoli died young, leaving a corpus of about 150 paintings and fortunately an imaginary interview conducted by Maurizio Cattelan in 2012 - in English - thanks to a montage of excerpts and quotations found of the artist. Because it is eloquent, it is transcribed below;

Branche de cactus, Domenico Gnoli, 1967

Maurizio Cattelan: We’re doing this on the occasion of your exhibition in New York. I understand the last time you had a show here was in 1969. Do you like America?

Domenico Gnoli: I love America. I lived here too but my links are exclusively Italian.

MC: You mean the background that informs your work?

DG: Yes.

MC: You were born in Rome. Does this mean that your paintings are still “Roman” despite their acquiring international status?

DG: Well, just like me, they are Roman by nature, not by vocation. A sort of inventory of the Rome in which I grew up, possibly more a Rome I remember than a Rome I know. An inventory of umbrellas, chairs, crates, the tables of the sidewalk cafés, fish and vegetables stocked in the shady intimacy of small markets, the solemn and dark laundries — everything, in short, that moves on the cobblestones of the narrow, unpredictable streets of the old Rome. And the smell, the noise, and then at last the night . . . the empty wine shops — the “osterie” with the odds and ends remaining from some informal gathering, some ready to close with the chairs on the tables so the floor can be swept, only one table still set with the chairs around it for the tired waiters’ dinners . . .and then the noise ceases, but the voices go on — the mocking wise voices of the Romans, the wise voices of a wise city.

MC: How was your childhood in Rome?

DG: There isn’t much to say about my childhood. I remember explosions of intense happiness, followed shortly afterwards by profound melancholy that always prompted remarks and comments from those around me on how remote my life was from my age. Therefore I rapidly lost all my respect for age. From then on, I always lived without any age, given that every year I used to repudiate it, choosing another one for the sole good reason that I liked it better.

MC: That’s great. You were changing your age every year?

DG: Yes. Why not? Life can be considered as a huge wardrobe, with so many dominos hung in its cupboards, one domino per year. Now I don’t see why I couldn’t change my mask in this wardrobe even twice a day.

Tie, Domenico Gnoli, 1969

MC: How did you start painting?

DG: Well, I was born knowing that I had to be a painter, because my father, an art historian, always presented painting as the only acceptable thing in life.

MC: If he was an art historian, I’m sure he was into traditional painting.

DG: Yes, he directed me towards classical Italian painting, against which I soon rebelled, but I never lost the taste and craft of the Renaissance.

MC: I can tell. It’s actually interesting because I always felt that you were somehow in the middle between the Art Informel generation and the one of Arte Povera.

DG: I know. For many years it was difficult for me to paint because I didn’t feel the informal painting that was then tyrannically dominating painters and art collectors.

MC: I can see that. Your work seems rather more indebted to Italian surrealism rather than Art Informel.

DG: Really? Would you call it surrealist?

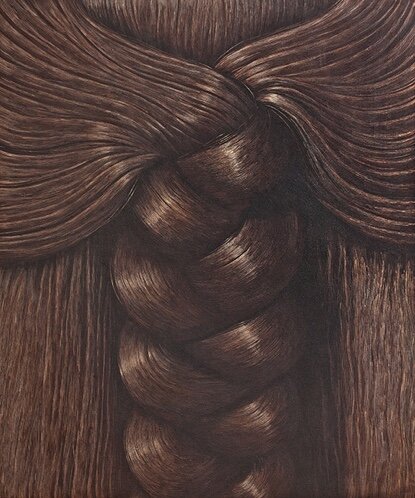

Braid, Domenico Gnoli, 1969

MC: Well, in a Giorgio de Chirico kind of way, yes. Your objects are a little metaphysical,wouldn’t you agree?DG: I am metaphysical inasmuch as I am looking for a non-eloquent painting, immobile and of atmosphere, which feeds on static situations.

MC: Right. But not in a stagy way.

DG: No, I never tried to stage, to fabricate an image. I always use given and simple elements, I don’t want to add or subtract anything. I haven’t even ever wanted to distort. I isolate and represent. My themes are derived from current events, from familiar situations, from daily life, because I never actively intervene against the object, I can feel the magic of its presence.

MC: You had a spell as stage designer, though. Do you think it affected the way you paint or perceive ordinary objects?

DG: I don’t know. I was passionately involved with the theater and created stage design for Barrault, the Old Vic, and the Schauspielhaus in Zurich . . . . However I couldn’t get used to the community and social life of a theatrical set designer.

MC: Yes. Painting is a much more private experience. And you don’t have to worry about your audience every night. Well, you actually do, but in a different way.

DG: An audience is perhaps unnecessary to the soul-searching mystic, but it is vital to the magician, the maker of prodigies. This is so because prodigy only feeds on prodigy, fantasy on fantasy. The performance on the stage has its reasons in the performance induced in thousands of separate minds and this second performance is no less prodigious than the first. Coming back to my work, let me state that I call prodigy all that is invented, all that begins to exist from the second it is conceived, it is the process not the results, the principle and not the fruits.

MC: So what’s your principle? Why are you doing this?

DG: Why am I doing this? But that’s the whole point. I am doing this because this is what really happens deep inside you. You begin looking at things and they look just fine, as normal as ever, but then you look for a while longer and your feelings get involved and they begin changing things for you and they go on and on till you only see your feelings, and that’s why you see this mess.

MC: But back in the 1960s there was the advent of the new media. Weren’t you tempted to explore these formats in relation to ordinary objects rather than rely on a traditional medium like painting?

DG: Oh, I know how pathetically inadequate my medium is, but unfortunately I dispose of no other.

Curly red hair, Domenico Gnoli, 1969

MC: No, no, I didn’t mean it like that. What I was trying to say was, if you were interested in ordinary objects, why not work on them directly rather than just try to paint them?

DG: I don’t know. All I know is that mine was a completely new theory about art, a new approach that made the pictures appear just like life does. But I don’t want to think that I am going to believe that I am a hell of a genius, or anything like that. The idea is formed spontaneously in the antechamber of my consciousness and I just have to give it pictorial presence. My life provides me with these images that become expressions of my daily experience.

MC: That is something that Pop artists were doing too. Did you like Pop art?

DG: Oh, yes. Only thanks to Pop Art, my painting has become understandable.

MC: Where do you think Pop art’s fascination for common objects comes from?

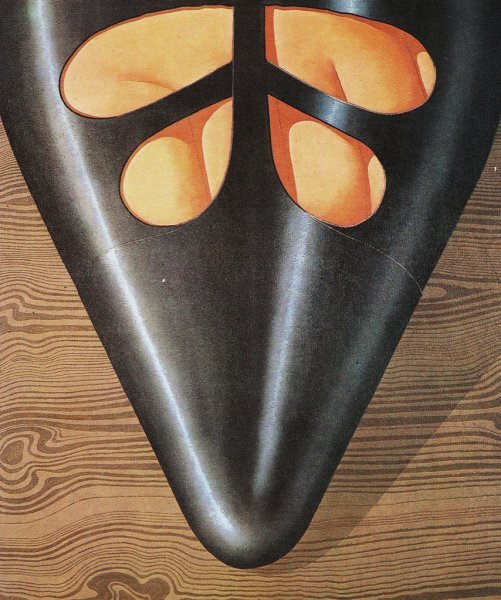

DG: I can only speak for myself but for me imagination and invention cannot generate something more important, more beautiful and more terrifying than the common object, amplified by the attention that we give it. An object alone, in front of me who is alone, exactly in front of me just as I would like to have in front of me someone who really interests me, in a good light to better observe it.

Shoe, Domenico Gnoli, 1969

MC: So the object is ordinary but not impersonal.

DG: No. It says more about myself than anything else, it fills me with fear, disgust, and enchantment.

MC: I hear you. I actually feel the same way about the magazine I’m doing now, Toilet Paper. I think there is a lot of me in there, but many people perceive it just as a smart move to reach a wider audience.

DG: If an artist has the possibility to contact an infinitely larger public through the pages of a publication, he should try to invest more rather than less and go as far in his effort to communicate his inner image as he can.

MC: Thank you. That really settles the issue for me.

DG: This is good.

MC: What questions would remain to be asked?

DG: For me certainly none.

L’inverno (couple au lit, Domenico Gnoli, 1967